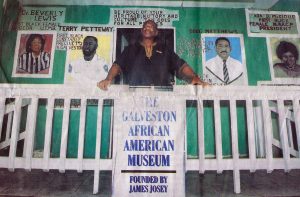

A visitor to the Galveston African-American Museum will find no reference to segregation, discrimination or such horrors as the lynching of Chester Sawyer a century ago this past June. The museum’s founder, Galveston native James Josey, had a different reference in mind: to highlight accomplished, island-born African-Americans.

“The museum is all about positive role models,” Josey said of the center at 902 35th St., on Galveston’s historically African-American north side of Broadway. “The whole purpose is to help young African-Americans be proud of their culture.”

Josey, 70, bought the two-story building and renovated it — from his own pocket — to honor African-Americans who succeeded both for themselves and for the community at large.

The Galveston African-American Museum opened its doors in 1999.

“I was thinking young people need a place to find out about their local history, not Martin Luther King, not Harriet Tubman, but local people, some of them people still alive who they could meet and talk to, shake their hand,” Josey said.

The building’s exterior, covered with portraits painted by two local artists, the late Jepter Lee Stephney, a Galveston-born commercial artist better known as Febo, and Emanuel Herron.

“I went to them, and I told him whose pictures I wanted on the building,” Josey said. “The people on the front are all BOIs. I tell young people, ‘One day you could be right there, you could be on the wall.'”

A ROUNDABOUT ROUTE

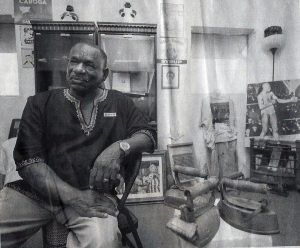

Josey’s path to creating the museum was decidedly circuitous.

After graduating from Central High School in the days when the island’s public schools remained segregated, Josey was drafted into the Army and sent to Vietnam, where he was injured during the 1968 Tet Offensive.

“Over there, I gained a new appreciation of people, that the bottom line is, we’re all the same,” he said inside the museum, surrounded by portraits of politicians and performers, pugilists and preachers. “What I found was, we may be different colors, but we all bleed the same.”

Coming home, Josey was hired on as a machinist with Todd Shipyards Corp.’s Galveston Division, where he worked the next two decades — and had expected to do so until he retired.

Todd Shipyards, though, began laying off employees at its Galveston facilities in the late 1970s, a precursor to the corporation’s August 1987 filing for bankruptcy protection. Todd shuttered its Galveston yard in 1990.

Josey had, in 1979, accepted an invitation to move to Southern California, where Todd’s Los Angeles yard was still doing well

“I was working as a machinist at Todd Shipyards and had a wife and three kids,” Josey recounted, referring to his wife of 47 years, the former Pearlie Goins, and their three daughters at the time. “They started laying people off in Galveston. I had an uncle, Fred Conley, who was a machinist at Todd’s San Pedro shipyard. He told me, ‘I can get you on.’ So I went out there and got a job.”

Josey soon bought a home in nearby Compton, a middle-class, blue-collar city that came to be known as the home of the seminal rap band NWA, whose album “Straight Outta Compton” inspired an award-winning film of the same name — and for gang violence.

COMING HOME

Josey returned to Galveston in 1991.

“My wife’s parents owned quite a few homes here on Galveston Island, and both had taken sick,” he said. “My wife had to help care for her mother, and that’s why we came back.”

He was shocked to see that the gang violence he thought he had left behind in Compton had taken root on the island.

“These kids were doing the same thing as they were doing in Compton, Bloods and Crips,” he said. “When I came here, it was going on strongly.”

Josey in response launched a program, Unity Within the Community, to refocus wayward youth, while also earning a bachelor’s degree in social work at Texas Southern University.

He soon found out he wasn’t alone in working to end the violence.

“I met Mr. Josey shortly after he returned from California,” said Sue Johnson, an African-American community activist. “In the early 1990s, there was an epidemic of youth violence around the nation and here in Galveston. The headlines were always talking about the violence. Something had to be done.

“Mr. Josey at the time was doing things like Unity Within the Community, which created an opportunity to find a different path.

“We pulled together and found people who knew about gangs and others who had been affected by the violence,” Johnson said. “People who worked with the youth and who had ideas on how to curb the violence.”

A COMBINED EFFORT

Unity Within the Community had begun simply enough with lumber and nails.

“The first thing I did, I saw a vacant lot at 38th and Ball and built a stage there,” Josey said. “One way to get through to kids is to have a festival with music and motivational speakers talking against drugs and gang violence.”

Other programs launched during the pivotal 1990s included Youth of Nia, which recognized young strivers and achievers, and Transformation Girls’ Rites of Passage, a womanhood training program. Holistic Community Development Corporation at the same time founded a similar program for boys.

“We realized we could affect change in the youth but that also had to involve the parents, so in 1997 we also founded the Family Strengthening and Empowerment program and offered support groups,” Johnson said.

The now-late Rev. James Thomas organized Midnight Basketball, which kept gangbangers and would-be gangbangers off the streets at the witching hour.

Youth Build, started by former Galveston Housing Authority Director Walter Norris, gave dropouts and gang members seeking a new direction job skills and employment renovating housing projects.

RAPPING VERSUS FIGHTING

Alfreda Houston, the late, former director of the St. Vincent Episcopal House, paid the rent for another Josey initiative: Jimmy’s Music Hall.

“Instead of fighting against each other over colors, we got them rapping against each other and dancing in competitions,” Josey said. “Kids were coming from all over the mainland to Galveston. They started looking forward to performing on Friday nights. The so-called Bloods and Crips were getting on stage and competing in rapping and dancing, and that made them able to talk to one another.

“Today, some of those kids have wives and kids of their own and I get joy when they introduce them to me, saying, ‘Mr. Josey, I want you to meet my wife, and these are my children.'”

The combined efforts paid off as gang-related violence on the island abated.

“When Mr. Josey came back to Galveston, he hit the ground running,” said Galveston County Constable Terry Petteway, whose law enforcement career began in the 1980s.

“It’s because of him and the others that a lot of the problems we were dealing with then, we’re not dealing with now.”

Reprinted from “Galveston County -The Daily News” article December 6, 2017 Author/Byline: TOM BASSING Correspondent

Section: News